The Database Novel

Before picking up Georges Perec’s Life: A User’s Manual, it had not occurred to me much that a novel could be, in essence, structured data.

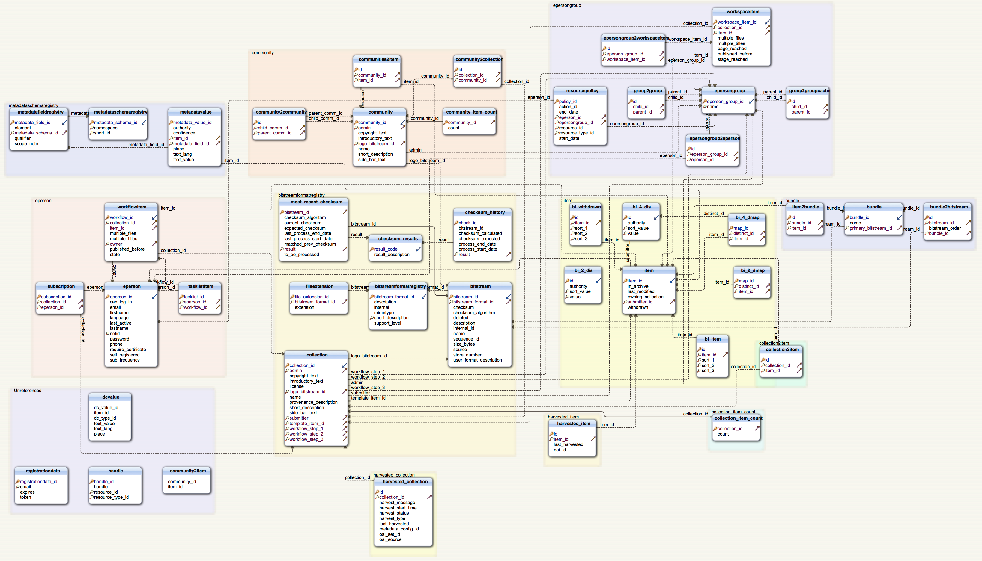

Or rather, it might have occurred to me insofar as books bring together predictable units: words make paragraphs, paragraphs make chapters, chapters comprise sections or parts (optional) and parts align to make an entire book. Though it interested me to consider that the elements of a novel, its content, the situations and items that inspire the plot or narrative might assemble as if the components of a relational database.

Or this is what comes to mind as I review the wikipedia section for this novel describing the constraints Perec used to craft his novel.

The constraints: These elements come together with Perec's constraints for the book (in keeping with Oulipo objectives): he created a complex system which would generate for each chapter a list of items, references or objects which that chapter should then contain or allude to. He described this system as a "machine for inspiring stories". There are 42 lists of 10 objects each, gathered into 10 groups of 4 with the last two lists a special "Couples" list. Some examples:

- number of people involved

- length of the chapter in pages

- an activity

- a position of the body

- emotions

- an animal

- reading material

- countries

- 2 lists of novelists, from whom a literary quotation is required

- "Couples", e.g. Pride and Prejudice, Laurel and Hardy.

As I read this book, I notice how modular it is. It is the story of an apartment building in Paris on one day, June 23, 1975. Each chapter explores a single apartment or part of the building, taking in the history of its owners and their relation, somehow, to the main character, Bartlebooth, a wealthy englishman who contrives a scheme for puzzle making that sends him around the world. As an object-oriented work of literature, I am not surprised that eminent computer scientist Donald Knuth has regarded this book as “perhaps the greatest 20th century novel”.

If this were a book review (which it is not), I would note that throughout these stories, I often find it hard to follow the “plot” as each chapter seems to fixate more on the details of objects and these objects are overwhelmingly the focus of attention, the glue that pulls together quick snaps of history and the interactions between residents and their predecessors: a list, a recipe, a painting, a sign on a door, a section of a catalog. In all of this clutter, I am routinely brought back to the images of the recently discovered Paris apartment locked in time. But it is this interesting mosaic of objects and detailed descriptions of them that shores up its unique method of composition.

The question creeps up to me, then: is it possible to write a novel first as if filling out a spreadsheet or set of form fields that feed into a database? To conceive of the objects necessary for a plot, assign them numbers, hierarchies, and a taxonomic spot in line from which to create a presentation from and then write the book? Or better (or worse, perhaps) have an algorithm write the book?

I am imagining that one might ‘query’ for the story, or the interaction between characters, or some plot arc:

SELECT c.dialogue, c.action, c.conflict, p.scenario, p.context

FROM characters c, plot p

LEFT JOIN observations ON observations.author_influence = c.author_influence

WHERE c.status = 'NOT DEAD' AND c.status = 'MYSTERIOUS'Silly as it sounds, it might make for an interesting project in language processing. Would anyone read it as they do Finnegans Wake, trying to locate meaning and structure in the incidental language of the one as they would the incidental plot and interactions of the other?