Introduction to Internet Marketing Content Studies Pt. 1: The Web is (still) not an API

What is it?

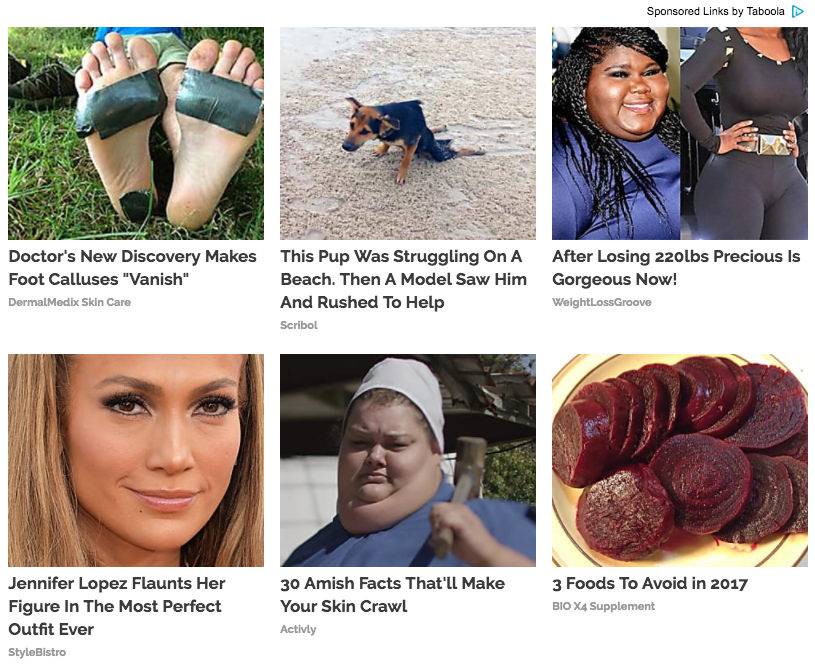

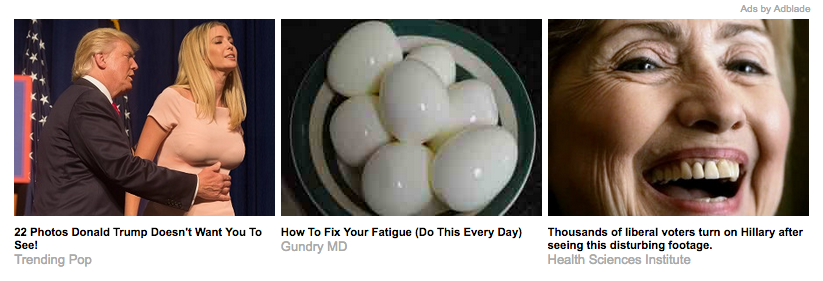

Suggestions from native ad networks such as Taboola, Outbrain, Revcontent, Content.Ad, and Adblade supply users of popular news sites with promoted articles or “content” on other web sites. Whether that content is valuable, authentic, “true”, or worth consuming is unclear. Whether the domains (e.g., TheViralDance, TheBuzzTube, EdgeTrends, Style Bistro) they point to are legitimate, reliable, or ‘real’ is also unclear.

Native ad content (also called “promoted links from around the web”, “sponsored links”, or “sponsored content”) is generally found bundled up in rows of two or three somewhere around the end of the article somewhere near the comments section. They provide their clients (the content providers which deploy them on their sites) a source of ad revenue. The content, it seems, is engineered to maximize numbers of clicks. And it points to sites that do not seem to provide anything else other than additional advertisements and additional promoted content. After a certain point, it’s promoted content all the way down.

Depending on the client, it might point towards other related content within that client’s website or network. More often it seems to point towards content that is absurd, false, or otherwise meant almost exclusively to render clicks without regard for the quality, value, or existential merit of the target content.

Why it’s interesting

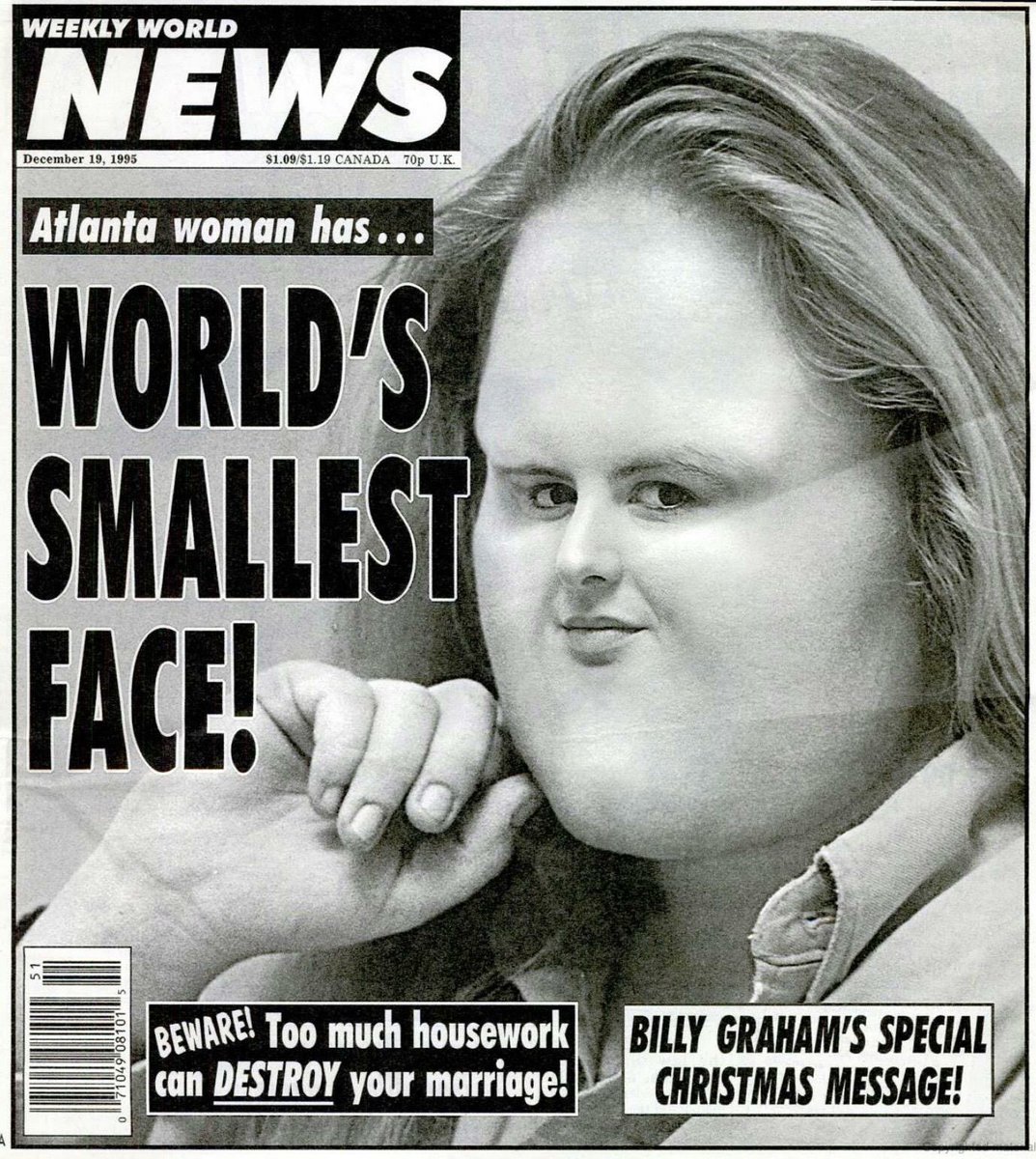

It’s interesting because it’s everywhere. It’s interesting because it’s engineered to be “interesting”. It’s interesting because it’s often so extremely lowbrow, trashy, and it’s a spectacle in itself to believe that anyone would click on these links at all. Their analog is supermarket tabloids like the Weekly World News found in the checkout line. Who buys those and why might give insight into who clicks on the clickbait.

Though why would this type of content be so ubiquitous if it didn’t provide results? Proof that people actually do click on this content is evident in the simple fact that these content seem to be proliferating rapidly.

It is also potentially has a role to play in the renewed focus on “fake news”, which now seems to have had consequences far outside of the expectation simply to serve as a spotlight for sponsored content on the web.

Because I found it interesting and because it is not a trivial matter (anymore), I wanted to collect it. But I certainly did not want to waste my time browsing the Internet manually to gather these contents. So I needed to have a process that would browse the Internet for me and collect these absurd nuggets of information.

The collection process

1) I put together a script using PhantomJS and Selenium as a headless browser that scraped 22 selected US websites (see the list here) with known “suggested content” on them once every 7 hours for about 60 days. The more absurd, the better. Also, I tried to select a diversity of editorial perspectives across these sites. I wanted a sampling of sites that had different political views to see if there was any correlation between the political inclinations of the site producers and the content that appeared via third parties (i.e., would the native content on each site support, more or less, the same political agenda, where applicable?)

2) On any given capture, I tried to avoid duplicates (defined by checking the headline of the content and the site it came from), to ensure we only got one of each unique piece of promoted content per site per scrape. But I left duplicates across different scrapes (or harvests) as there might be good information about frequency of a certain piece of content such as which content appeared the most across multiple sites and scrapes.

3) Images were downloaded from the source and given a filename generated by creating a sha2 hash of its original URL. The metadata were stored in a mongodb database and is nightly pushed to a csv file.

But Why?

It is possible that we could learn something about about how these services work by laying out a large number of their products in a search-able database and analyzing them for patterns. I also wanted to explore the connection between types of websites and the types of ads that were served up (e.g., which sites had more quasi-true ads as opposed to others). Finally, I wanted the longitudinal view. That is, to see which ads came and went, for how long, and in what intensities. Also to see if the same headline (or derivations of types of headlines) were applied to a number of different images or vice versa the same image applied to many different headlines?

The why is to be seen in later posts about this. Which will be linked here.

Some main challenges:

The final purpose of this post is to detail some of the difficulties in gathering this content.

1) The web is still not a great API (and it may never be): Because the scraper relies on pulling top n articles from a number of different sites and then scraping the third party content from a sampling of those articles, it will stop working for sites where the layout has changed. Or they might drop an ad content provider, and so that will have to be updated. All of these things might be tested for and logged properly. But to some extent, it’s not worth that much effort for an experiment like this. It’s reasonable to scrape one site repeatedly because you can tailor your script to that site and easily reconfigure it when it changes. But when you are trying to apply a generalized scrape across a number of different sites, you can only do so much when any of those sites change to accommodate the change. In this scenario, adding another site to the scraping queue does not scale linearly unless you’re willing to compromise on what you are able to collect, and some sites just won’t fit into the regularly scheduled program.

2) Idiosyncratic JavaScript: Sometimes a sites marketing strategy involves overlays on top of the content before entering the site (e.g., subscribe to get this content, additional ads that users have to click off of to get to site content). This post certainly has more to say about that.

3) PhantomJS is not totally stable (and it may never be): In many ways PhantomJS is great, but it still has a few issues. Namely that it fails or succeeds inconsistently depending where it is run from and what version you are using. I found that even though I had it running quite well and reliably on my laptop (with OS X 10.11), it was much less reliable when run on an Ubuntu server (16.04) running the exact same version of everything the script depended on.

It had a much less greater rate of success scraping native ad content from the article pages on the Ubuntu setup than on the mac setup (hovering around dropping 50% of pages on the former most likely on account of the third party JavaScript not loading up properly before attempting to scrape – no matter how long it was set to wait before scraping). It is not clear why this was the case, and I think after a bit of troubleshooting, I just get the sense that PhantomJS is trying to do some complicated stuff, and can’t be relied on to give a consistent headless browser experience across the board.

For the purposes of this experiment, the workaround was to just force the scraper to grab more than it probably would be able to properly ingest, in the hopes that its yield, scrape-for-scrape would be sufficient for a longitudinal analysis even though it fails on half of the attempts it made during every pass.

Where to next?

With a good sampling of promoted content from different domains, sites with different political inclinations (or none at all), and over time, we might pursue some of the following courses of analysis:

1) Understand content on a site-per-site basis or across sites: As mentioned above, it might be interesting to see what kind of content is more prevalent on different sites and to see if any of this correlates with the political agenda where it was originally displayed.

2) Image analysis: Are these images in possession of some “clickbait-ability” factor? What happens if we incorporate a neural network to see how machines view the images used in native advertising?

3) Plumbing the evil depths: What happens when you get robots to click on the links to these sites, and follow that rabbit hole down to the nauseating content hell it has created?

4) Develop an “ontology” of suggested content: Or don’t.

5) Analyze the language used in the headlines: Look for patterns in language use and topics. Perhaps use the building corpus of native ad headlines as the basis for generating artificial image and headline pairs. A fairly amusing project for this using articles from well known clickbait sources like BuzzFeed can already be found here.